tags - | physics | classical_mechanic |

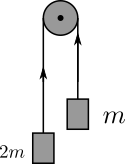

In a typical highschool situation, when solving a diagram like this, we would be neglecting the friction and the weight of the rope. Now, accounting for friction is a story for another time. But let’s look at the rope more closely, what does it mean to “neglect the weight of the rope”?

Well, it means we pretend the rope has zero mass, and even though it’s accelerating just like the weight on the pulley, it will take 0 Newton to keep up with the weight $ 2m $ and $ m $.

Don’t believe me? Well, let’s calculate the force on the rope.

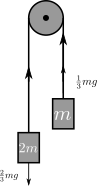

Because the magnitude of acceleration is the same all throughout the system. The net force on the whole system is $ 2mg - mg = mg = 3ma $ which leads to $ a = \frac{1}{3}g$.

Zooming in on the two weights, we notice the rope has to provide force with magnitude $\frac{3}{4}mg$ in order for the two weights to have the same acceleration. Now, using Newton’s third law, we can also infer that the weights pull on the string with magnitude $\frac{3}{4}mg$

Therefore, since the string is pulled in opposite direction with the same magnitude, the string receives zero force. QED.

So the string receives zero force, precisely because we pretended that the string’s mass is zero. So no matter how big the acceleration of the string is. $F = ma = 0 \cdot a = 0$

But what if we don’t pretend?

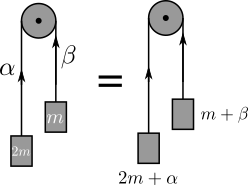

What if we don’t pretend the string’s weight is zero? Now, we don’t want to just say “ let the string on the left have weight $\alpha$ and the string on the right $\beta$ “ and start our analysis, because that’s almost1 the same thing as having two mass $2m + \alpha$ and $m + \beta$

No, in order to make our situation more interesting, let’s say we’re in a situation where the string’s gravity is ignored, but the string’s inertia is accounted for.

A hypothetical situation where this could happen is when the string’s inertial mass is not small enough to ignore, but it’s

- orders of magnitude smaller than the weight and

- gravitational acceleration is so small that the gravity doesn’t act that hard on the string compared to the weight.

Now, is this a hypothetical situation just for funsies? Probably, but I’m more of math major than a physics major, so what can I say?

To make the analysis easier, let’s hold the pulley in place, and analyze the moment we let go, so all the parts of the system have initial velocity 0.2

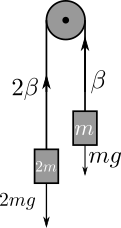

Furthermore, let’s say the left part of the rope has mass $ 2\beta $ and the right part of the rope $ \beta $. Hopefully the reader will be able to see the way to generalize this to arbitrary proportion.

One final thing before the analysis begins, I want you to think intuitively about what will happen. Will the rope receive any force? If so, how much? Will the weights go slower? faster? just the same?

Now, since the acceleration is still the same throughout the system

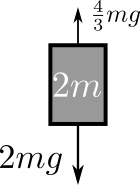

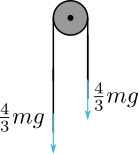

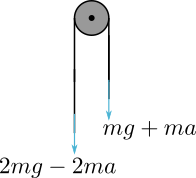

\[mg = (3m+3\beta)a\]in order keep the algebra clean, let’s try to keep the $a$ for as long as we can. Now, zooming in on the weight, we would see that the string on the left would pull with magnitude $2mg - 2ma$ (net force on $2m$ would be $2mg - (2mg - 2ma) = 2ma$), and the string on the right would pull with $mg + ma$. Now, again, using Newton’s third law, we can zoom in on the string and figure out it’s net force.

Finding the net force

\[2mg-2ma-mg-ma=mg-3ma\]Substitute $mg$

\[(3m+3\beta)a - 3ma = 3\beta a\]So the rope, now accounted for it’s inertia, does receive force, in exactly the same magnitude that would make it have the same acceleration of the weights.

Thoughts

I think it’s always a healthy exercise to go outside the textbook for a second and put some messy, real world complication back in. Although some problem, when generalized, makes that problem from “solvable” to “impossible” (e.g. 2-body to 3-body problem), some problems pushes your analytical skill to the test, and it’s always a good habit to try to generalize once you have some foothold with the special case of the problem.

You could also think about when the pulley is in motion (the initial velocity is not zero), air friction, etc etc. But I think this is enough exposition for a high school textbook example, I’ll think about more complicated stuff for better, more interesting examples.

-

almost, since the string’s mass will change with time (left side becoming heavier, right side becoming lighter) ↩

-

if there is velocity, the mass of the rope would be a variable mass system, a complication for another time. ↩