When reading the Feynman Lectures(FLP)1, Mr.Feynman introduces principle of virtual work, where you take advantage of the fact that an equilibrium condition is basically a reversible machine, so you calculate what the energy expended would be if that “machine” where to operate, set that to zero, and use that information to try to find some information about the forces.

There’s also a trick that he uses on the last example, the trick is more mathematical than physical, as Newtonian mechanic kind of are. And today I want to show you a generalization of that trick, and show you where I used some of this technique

First, the example with the hidden trick

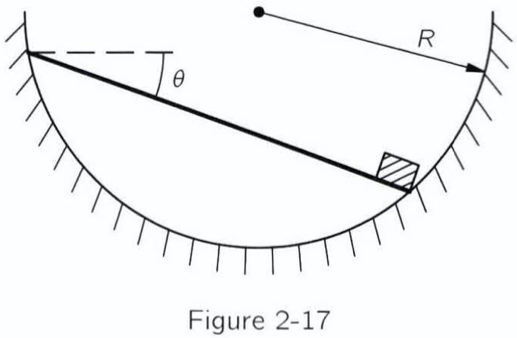

The rod is 8 inches, a 60 pound is sitting at the mid point on the rod, and a 100 pound weight is sitting at 2 feet from the left on the rod. How much counter weight, pulled by an ideal pulley is required to balance the weights?

If the system is just in balance, there will be no work if the system was perturbed just a little. So Mr.Feynman says (italic is mine)

suppose it(the counter weight) goes down 4 inches—how high would the two load weights rise? The center rises 2 inches, and the point a quarter of the way from the fixed end lifts 1 inch. Therefore, the principle that the sum of the heights times the weights does not change tells us that the weight W times 4 inches down, plus 60 pounds times 2 inches up, plus 100 pounds times 1 inch has to add up to nothing:

then setup the equation, blah, blah, normal algebra, the counterweight needs to be 55 pound. What’s interesting here is that Mr.Feynman kind of “cheated”, if you pull W 4 inches, the weight don’t go exactly 2 or 1 inches, because the rod acts like a circle, and the weights will go on a curve.

However, because the distance is said to be relatively small, it’s approximately, 2 inches. And if you take it as an infinitesimal amount, it is analytically exact (if you think of all the objects in the diagram as ideal, mathematical object).

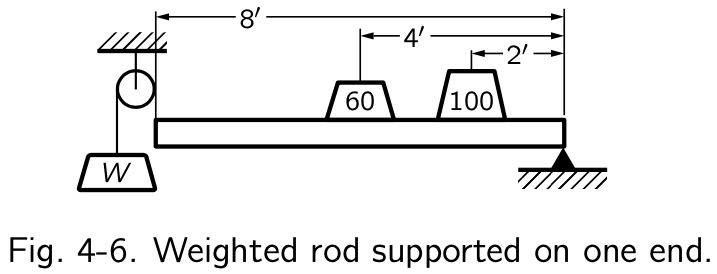

There’s a generalization of this technique, which can be shown when you analyze what happens when you make a very small triangle on a circle

Take a look at this diagram. The l parameter is the distance between the two points on the circle, and theta is the angle the first point makes with the horizontal line (if you’re confused, try dragging the sliders).

I’ve also measured the angle AB’C and the angle AB’E, since E is on the line that’s tangent to the circle, AB’E is always 90 degrees.

Now, drag that l slider as close to the 0 as you can and watch what happens to AB’C as you go closer and closer to 0 (but don’t put it at zero)

…It approaches 90 degrees.

Also, notice how CFB’ and EFB’ are getting harder and harder to distinguish, and this is where the trick comes in. You argue that due to this pattern, when l approaches 0, AB’C approaches 90 degrees.

Now here’s the key construction, what you do is you take a length that is infinitesimally small, that is you take that “approaching” process and imagine there is a triangle at some end of that process. The property of that triangle is that it would be on the circle, but the angle it makes with the origin of the circle would be 90 degrees.

This is not possible with any length of a real number, hence the name impossible triangle2. However, with a limiting process, you can construct a triangle that would have this property if the end of that process is somehow reached.

Now, there is two3 edge cases, one is when theta is 0 and one is when theta is 90, since it gets a bit tricky to imagine the triangle when the tangent is a vertical (theta = 0), it’s just easier to say CB’ is a vertical line and not worry about the point F. Same thing with the theta = 90 degrees, it’s just easier to say CB’ is horizontal line, and not worry about the rest.

This is a pretty important edge case, as Mr. Feynman used it in his example. The rod is at 0 degrees with the vertical, so when you make a perturbation with the rod, the small triangle just becomes a vertical line, and the rest of the argument can now be followed.

A similar construction can also be found on a 3Blue1Brown video here.

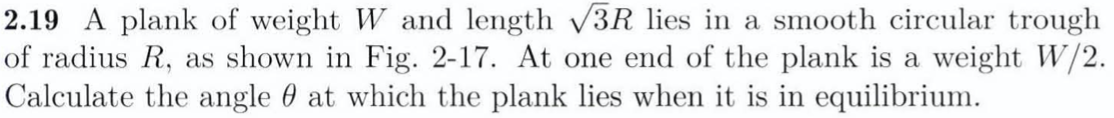

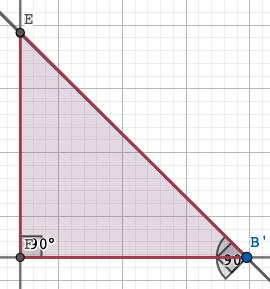

I’ve used this technique quite a bit when I was solving Chapter 2 of the Exercise for the Feynman Lectures (amazon link)

All the solutions that I posted so far can be found here, however, here are some problems that have been the key trick in solving them.